Tiffany Nassiri-Ansari

In Conversation With, the Lancet Commission on Gender and Global Health’s seminar series, returned with a fourth episode on June 22nd. In Gender activism, politics, and intersectionality in the era of COVID-19, Commissioner Fran Baum examined the intersectional inequities exacerbated by the pandemic and invited colleagues to share their insights from studying the structural violence experienced by many throughout the pandemic. Baum, Professor of Health Equity and NHMRC Investigator Fellow at University of Adelaide’s Stretton Institute, was joined by three colleagues:

This webinar was co-convened with UNU-IIGH and the Gender & Health Hub. Commissioner Baum and speakers were joined by fellow Commissioners and livestream audiences on Zoom and Twitter. A recording of the hour-long webinar is publicly available on the Commission’s YouTube channel.

Baum began the session with an overview of the many inequities that predated the pandemic but were undeniably worsened by COVID-19, with compounding factors such as gender, class, caste, race, disability, and sexuality. She identified structural violence as the overarching theme of pandemic response, evident in the “massive vaccine inequity” seen around the world. At the time of her comments, for instance, only 13% of Nigeria’s population had received a single dose of any vaccine, compared to the vaccination rates of high-income countries which tend to hover between 80-90%>. Even within those countries however, she noted that “the picture would be very different” if these rates were broken down to focus on people with disabilities, people of different sexualities, and other marginalised populations.

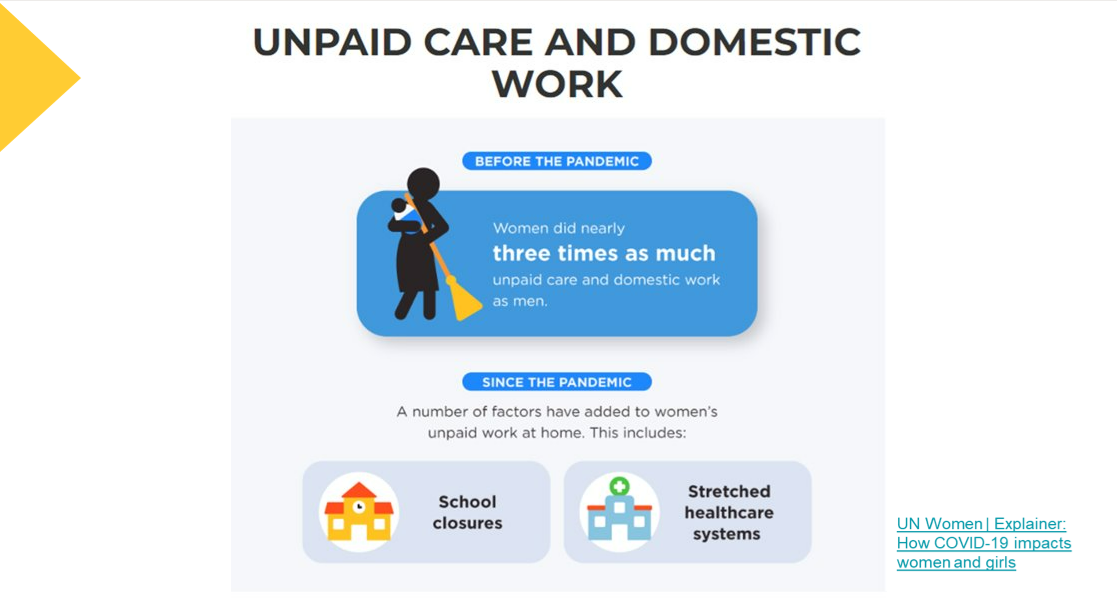

Beyond vaccines, the pandemic has generated gendered impacts that have disproportionately affected women and girls. Baum touched on women’s involvement in front line occupations, increased risks of experiencing violence during lockdown, additional burden of navigating care and work duties at home, and findings which suggest that women have been more affected by pandemic-related job losses and employment insecurity. Trans and gender diverse individuals have also faced gendered impacts in their experiences of the pandemic, with “the normal structural systemic inequities… [becoming] more pronounced”.

To shed light on these experiences of the pandemic, Baum swiftly moved into the panel discussion, which focused on better understanding some of the challenges that emerged during the pandemic through an intersectional lens.

Between the three of them, the panellists brought to the discussion insights from an examination of COVID-19 experiences in 17 case study countries, experiences of community engagement with Dalit and Adivasi women, and compelling arguments for the importance of narrative.

Musolino began with a focus on gender divisions in the care economy which emerged as a consistent theme across the 17 case study countries she recently analysed with colleagues at Stretton Health Equity. With women making up approximately 70% of the global health and social care workforce, the burden of care during the pandemic fell primarily on women shouldering paid and unpaid care responsibilities. The intersection of gender with class, caste, race, and more exacerbated the impacts of this burden for many, such as women of colour in the United States who were disproportionately represented in jobs which were deemed essential and necessitated continued work outside of the home even during the worst waves of COVID-19. Women employed in low-paid and precarious roles as caregivers for the elderly faced “some of the most deadly outbreaks”, but the informal nature of their employment often “meant that workers did not have access to paid sick leave and other entitlements, further increasing the risk of illness and spread”.

Utilising a political economy perspective, Musolino argued that “the COVID-19 pandemic is intrinsically linked to local and global economic and political histories”, with the legacies of colonisation, slavery, and patriarchy evident in the continued exploitation of care worker in countries “which often rely on and exploit groups in poorer neighbouring countries” as evidenced by the example of Peru’s treatment of Venezuelan migrants informally contracted to be maids and carers. Migrant and undocumented workers, both in the care economy and outside of it, often have little to no access to social security or rights, are more vulnerable to exploitation and abuse, and face harsher public health measures than the majority of other workers as seen in the case of long-term residential aged care workers in Singapore. However, in the latter example, Musolino also highlighted how swift measures were put in place by the Singaporean government to support care workers once the virus began to spread in aged care facilities.

Civil society activism tends to play a role in such stories of good practices, with Musolino crediting civil society not just for playing a role in political decision-making but also engaging in public discourse to raise awareness, fact-check misinformation, combat fear and stigma, and amplify the voices of marginalised groups by “pushing back against the politicisation of such identities during the pandemic”. However, different actors within the wider umbrella of civil society also feature prominently in cases of bad practices, such as anti-vaccination movements which have “lobbied governments and industry bodies to influence such things as withdrawal of mask mandates”.

Ultimately however, Musolino emphasised the importance of civil society activism as a force for good, highlighting the role South African and Indian civil society groups played in ensuring access to vaccinations and “engaging in broader issues around politics and power… to highlight intersections of oppression during COVID-19”.

Samy drew on her experience working with the National Federation of Dalit Women to speak on the role of civil society in the Indian context, and emphasised the influence of India’s caste system – “the longest surviving social hierarchy” – in individual experiences of the pandemic. She identified Dalit and Adivasi (tribal) women as “being at the lowest rung of the caste and gender hierarchies”, thus bearing the brunt of the exacerbated inequalities brought forth by COVID-19. The country-wide lockdown announced by the government in the early days of the pandemic had immediate effects on these marginalised groups, with Samy estimating that 90% of the internal migrants who lost their livelihoods and shelter overnight as a result of the lockdown belonged to Dalit and Adivasi communities. With no assurance of food or transport from the government, Samy recalled how “thousands of families – women, children, babies – walked back [to their villages] with several people dying of starvation en route”.

The impact of the pandemic on Indian women was immediate and devastating – while 73 million women were found to be living in conditions of extreme poverty in 2019, by 2020 it was estimated that the number had swelled to 110 million. In a call-back to Musolino’s earlier comments about women occupying low-paid and precarious roles, Samy commented that most workers in the unorganised and informal sector belong to Dalit and Adivasi communities and were disproportionately affected by the economic impacts of lockdown. With the pandemic threatening gainful employment and exacerbating unpaid care burdens, marginalised women, women with disabilities, and trans women found their labour market participation substantially affected.

Beyond the economic impacts, Samy identified a “shadow pandemic” in which guidelines to social distance coincided with “the highest ever” incidence rate of violence and sexual harassments against marginalised women, who were “further distanced, discriminated, and distressed with no access to essential services and rights whatsoever”. Many girls and women were also forced to drop out of school due to lack of access to online learning platforms and economic burdens; the National Federation of Dalit Women partnered with these young women and girls to strengthen collective agency and leadership skills during the pandemic, providing opportunities for them to advocate for pandemic relief such as dry rations and free shelter. These young women and girls swiftly started engaging with the heads of village councils, advocating with local authorities, and building social capital in communities where people “who were earlier dismissive of our very being now respect and look up to us as leaders”. In the context of increasing depoliticisation and government crackdowns on civil society, Samy’s final message was a reminder that “inequality is political and therefore our efforts to overcome inequity and inequality also have to be political”, as demonstrated by the young women and girls who were able to organise and challenge political forces to advocate for change.

The intersection between lived experiences and policy change is one Popay also explores through the COVID-19 Other Front Line Global Alliance, an online platform which highlights the stories of “groups bearing the brunt of social injustice… and [brings] the storytellers into conversations about the impact of the pandemic”. The platform was established based on the observation that insufficient attention was being given to “lived experience narratives that are not generated through research” in conversations surrounding COVID-19. Inspired by Maya Angelou, Popay stressed that “all our stories help us to understand the nature of social problems and begin to think about appropriate solutions”, with stories featured on The Other Front Line supporting the narratives shared by the other two panellists, particularly on the “intensification of [women’s] roles as carers” as well as unsafe living and working conditions. Other stories, however, showed “what equity might look like” and detailed “deepening social relationships in families and communities”; while Popay acknowledged that positive stories do not negate any of the negative experiences shared to the platform, she pointed out the value in understanding that these different perspectives can coexist, showcasing strength and resistance in different ways.

While these stories hold potential for informing recovery plans, Popay noted that narratives are primarily used by civil society and rarely given value by policymakers and academics alike, who tend to view them as “simply anecdotal”. In closing, Popay acknowledged challenges such as digital inequalities and language barriers which might limit the stories shared on The Other Front Line and other such platforms, but called for a democratisation of these spaces to enable the identification of common interests “in as many ways as we can” so that storytellers do not merely experience social injustice, but are given a way to become part of the solution as well.

A range of audience questions were acknowledged, touching on gendered environmental risks, men’s COVID-19 health risks, and collective practice of care. Due to time constraints, the panel was only able to address the latter in detail.

Can collective practice of care and activisms demonstrate change by challenging the dominance of neoliberal concepts of self-care and individual responsibility?

Drawing on her years of experience and learnings from The Other Front Line, Popay agreed that such practices hold promise but cautioned against the risk of “narratives of community care and powerful reciprocity” leading to a shift in responsibility from the public sector to communities. Models of community-driven collective care are insufficiently resourced, and Popay warned that “the risk is that the next iteration of the welfare state post-pandemic in countries that did have good welfare provision will be this DIY model”. Moving forward, she emphasised the need for sufficient financial and material support from the public sector to continue resourcing these community-delivered models.

In closing, Baum thanked the panel for raising these important issues about intersection, not just for public debate but also for Commissioners to keep in mind as they work to produce a final report that is sensitive and inclusive for all.

Tiffany Nassiri-Ansari sits on the Secretariat of the Commission and serves as a Research Assistant at UNU-IIGH.

Tiffany Nassiri-Ansari

The Lancet Commission on Gender and Global Health’s seminar series returned with a new season, In Conversation With, on April 29th. In the first episode, Commissioner Nina Schwalbe hosted a panel discussion on the importance of gender in promoting immunisation to mark World Immunisation Week 2022. Schwalbe, Principal Visiting Fellow at the United Nations University – International Institute for Global Health (UNU-IIGH) and Adjunct Assistant Professor at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, was joined by a panel of five speakers:

This webinar was co-convened with UNU-IIGH and the Gender & Health Hub. Commissioner Schwalbe and guest speakers were joined by facilitator and Commission Co-Chair Prof. Pascale Allotey, fellow Commissioners, and livestream audiences on Zoom, LinkedIn, Twitter, and YouTube. A recording of the ninety-minute webinar is publicly available on the Commission’s YouTube channel.

Allotey opened with an introduction to the In Conversation With seminar series, which allows Commissioners to deep dive into “a critical area of global health… that is bereft of gender considerations” in search of challenges, possible solutions, and good practices. Beyond facilitating dialogue with experts on the subject, each webinar also aims to leave audiences “stimulated and inspired to push harder and further in [their] work towards achieving equity and social justice with the goal of health for all”. Right off the bat, she also addressed the elephant in the room: the all-women panel for this session had been assembled in response to the fact that “several male colleagues noted that sex and gender are not priorities in this space,” a claim challenged by each and every speaker based on their experiences and expertise.

With the scene thusly set, Schwalbe began the session with a brief presentation that highlighted evidence on gender and vaccination, with data based on an analysis she had been involved with while serving as the United States Agency for International Development’s (USAID) director of vaccine access and delivery. During her tenure, Schwalbe oversaw the Biden administration’s donation of a billion vaccines to COVAX, and witnessed first-hand how “gender affects the entire vaccine value chain, starting with production and design” all the way through to delivery.

Data collected from the early days of vaccine delivery revealed that supply constraints and prioritisation determined whether more men or women were vaccinated; more men received early access to COVID-19 vaccines in countries where the military was prioritised, whereas the inverse was true for women in countries where healthcare workers received priority. However, as supply constraints eased, Schwalbe and team were curious to track the gender distribution of vaccine recipients based on the hypothesis that adequate supply would lead to “numbers more reflective of a country’s population structure”.

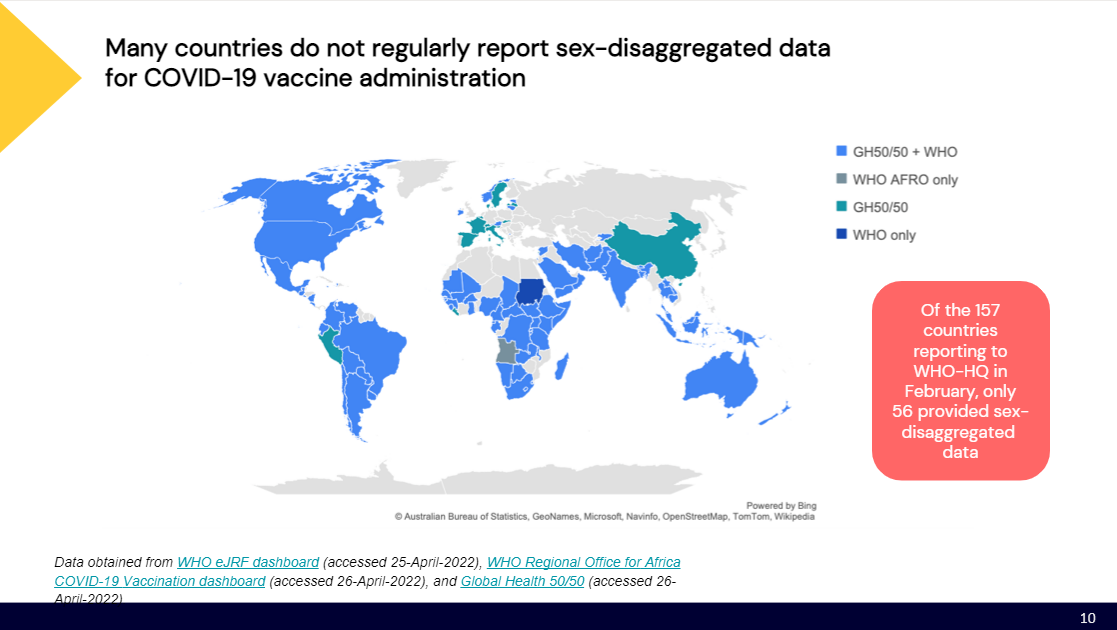

Turning to the WHO’s COVID-19 Dashboard “more than a year after vaccines were made available in most countries,” they found that some of the sex-disaggregated data in the database were more than a year out of date. The data that Schwalbe and team found were “flawed, inadequate, and outdated,” with only 56 out of a total of 157 countries providing data to WHO reporting sex-disaggregated data in January or February 2022.

Schwalbe summed up the situation thusly: “Despite binding commitments by the UN and requirements by COVAX, sex-disaggregated data on vaccines are simply not being reported by countries regularly, consistently, or in real time”. This lack of sex-disaggregated data is only one of the many gender barriers to immunisation, which the aforementioned USAID analysis concluded “were well-documented prior to COVID-19″. Challenges such as literacy and education gaps, work and domestic care obligations, limited mobility, and lack of decision-making power in the household were found to be relevant across all settings, ranging from low- to high-income countries, and these issues “strongly map to the current delivery challenges for COVID-19 vaccines”.

The fact that insufficient measures were taken to preempt these well-known gender barriers to immunisation is discouraging for the social determinants of health, Schwalbe cautioned, noting that “the outlook for measuring other determinants is bleak” if we cannot get something as simple as sex-disaggregated data reported regularly. Relevant mechanisms are in place, with countries using electronic reporting forms such as DHIS2 and fulfilling mandatory WHO reporting requirements through the monthly eJRF system, but “we need to bang the gender drum loudly and repeatedly so that every public health strategy is underpinned by a consideration of gender and other social determinants”.

Wrapping up her presentation, Schwalbe had one final message for the global health community which walked the line between grim and optimistic: “Given the billions of dollars spent in response to COVID, if we don’t come out of this pandemic with a better data system that allows real-time reporting of sex-disaggregated data at a minimum, we have failed. That said, we can use the evidence we have to double down on gender programming as a cornerstone of an equitable response”.

Allotey opened the floor for initial reflections from Schwalbe and fellow speakers following the presentation, posing a question on the problems with data collection: “Is it an issue of quality, access, or negligence?”

Schwalbe opined that the problem is all of the above, necessitating a push-and-pull strategy. She noted a push to invest in country-level data systems, but suggested that we need to go one step further and add a pull incentive by making gender- and sex-disaggregated data a matter of policy – “it should be a mandatory requirement for countries, full stop”.

The question of mandating sex-disaggregated data was one which Schwalbe and team explored in depth during her tenure at USAID, pondering the extent to which they or other mechanisms such as COVAX could make this requirement a condition of aid. Ultimately, Schwalbe felt that reporting requirements must be complemented by advance notice and sufficient support. “If you’re going to make it conditional, you have to set a deadline in the future that allows countries to get up to that point whereby they can meet the deadline,” she recommended, and noted that there is a broader discussion about accountability and where the responsibility to set requirements and monitor compliance lies. Closing out this section of the webinar, she posed a question to both the WHO and WHA: Why, despite repeated calls over decades, is sex-disaggregated data still not a hard and fast requirement?

“Tell us a little bit about how you use data to inform your work in Ghana.”

Moving onto the main event, Schwalbe introduced the three sections of the panel discussion: data, barriers and enablers, and solutions forward, with a Q&A session slated halfway through. Dr. Akosua Sika Ayisi (Ghana Health Service) began the data section with a case study of how Ghana successfully used data to inform and adapt the country’s vaccine rollout, particularly for women and healthcare workers.

Ayisi stressed that “data is the starting point of the gender discussion” in her introduction to Ghana’s electronic health database system, an investment which has paid dividends in real-time gender-disaggregated data. Beyond mere collection, Ghana actively uses data in a dynamic approach that allows for swift identification of and action on new issues as they arise. The country’s database is complemented by routine research, such as a study carried out by to assess the willingness of healthcare workers to participate in clinical trials for or accept the COVID-19 vaccines. Such studies among healthcare workers serve as fertile grounds for gender analyses given the increasing feminisation of health workforces around the world; Ayisi noted that in Ghana alone, women make up roughly 60% of the health workforce. The pre-rollout study carried out by Alhassan et al. revealed that women in the health workforce were up to 11 times less likely to accept a COVID-19 vaccine as compared to their male counterparts, and Ayisi credits findings such as these for Ghana’s preemptive development of “a very aggressive risk communication campaign aimed at health workers” which has now led to 90% of the country’s healthcare workers having received at least one dose of the vaccine, with the majority being women.

Data also reveals valuable information and crucial differences within, not just between, populations. Initial data showed that Ghana’s overall vaccine campaign had achieved comparable coverage between men and women, but the figures between urban and rural recipients were skewed, with those in urban areas making up roughly 62% of vaccine recipients while those in rural areas accounted for only 38% . Data analysis also revealed that of the women who had received vaccines, the majority of them were urban women working in the formal sector. This intersectional analysis led to concerted efforts to better understand the barriers to immunisation faced by rural women, informed by rural women themselves who revealed in focus group discussions and key informant interviews that static vaccine centres which necessitated travel and consumed time due to their fixed locations and long queues were the primary barriers for rural women who could not step away from their day-to-day responsibilities of informal work and caregiving. Ultimately, this combination of real-time data and stakeholder engagement allows Ghana to develop flexible, dynamic, and responsive rollout strategies which are continuously reviewed to ensure that no one is left behind in the nation’s vaccination campaign.

“What do you think it will take to make gender-disaggregated data a norm in practice and policy as we’ve just seen in that example from Ghana?”

This is “certainly the kind of model that we want to see,” Ms. Jamille Bigio (USAID) said in her remarks following Ayisi’s intervention, going on to outline how USAID is taking steps to support a “standard of practice” in which data is not only collected, but analysed and used. At the global level, Bigio stressed the need for WHO, UNICEF, and other UN agencies to not only set international standards for gender indicators, but to ensure and support the integration of these indicators into health information systems. Echoing Schwalbe’s call to provide the necessary support for countries to meet such standards and requirements, Bigio shared some known challenges countries have faced in reporting sex-disaggregated data in a timely manner; chief among these challenges were data backlogs in the move from analog to digital, lack of technical familiarity and assistance, and training for research clerks in this shift towards digital. These are all issues USAID is actively providing support on, but Bigio urged donors to collectively step up in this arena and identify possible ways to support digital solutions as well. The goal, ultimately, should be a global system of data collection which allows for widespread and long-term analysis of both quantitative and qualitative data.

While numbers matter, Bigio emphasised the utility of a qualitative tool such as Johns Hopkins’ COVID-19 Behaviours Dashboard which surveys knowledge, attitudes, and practices around COVID-19. In so doing, the dashboard has revealed gender differences in vaccine confidence and uptake in many countries, with the data enabling more tailored interventions to promote vaccine demand. A mixed-methods approach allows for not only the identification of inequity but also an understanding of why it exists and how best to reduce it, with Ayisi’s case study of Ghana serving as the perfect example.

Schwalbe invited reflections from fellow panellists at this point, all of whom touched on the demonstrated importance of gender-disaggregated data. Ms. Sarah Goulding (DFAT) in particular pointed out that the identified challenges are indicative of the broader struggles faced by those attempting to collect sex-disaggregated data at large, and offered her thoughts on why so many peers believe that gender is not a barrier to immunisation. Given that most immunisation research and implementation in recent decades has focused on early childhood immunisation, Goulding conceded that surface-level analyses of the data indeed suggests that there is no significant difference in vaccine uptake between boys and girls. “There’s been this myth that gender doesn’t matter to routine immunisation,” she acknowledged, but closer intersectional analyses reveals that challenges faced in the COVID-19 vaccination rollout are not unique, with women, girls, and disabled children in hard-to-reach populations bearing the brunt of immunisation inequity.

Offering some final thoughts on data, Ayisi stressed the importance of making sex- and gender-disaggregated data a priority right from the start, in policy-making and agenda-setting spaces, to ensure that enough resources are made available to not only implement the collection of such data but integrate it into routine health systems.

“With the benefit of hindsight, what would you have predicted as the barriers and enablers, and what are your key takeaways?”

Prof. Mira Johri (University of Montreal) was invited to start the discussion on barriers and enablers, and drew from her research on routine immunisation, particularly in the Indian context, to point out that many of the challenges faced in the COVID-19 vaccination rollout are neither unknown nor unexpected. “Over a 25-year period, we’ve come to realise that social norms, values, and beliefs that shape gender and other forms of access imply restricted agency” through a number of determinants, yet this knowledge was not applied at the policy-making level. Johri stated that this raises the question of who sits at the table in decision-making spaces, a group which is “often very male, often very privileged”.

In terms of what could have been predicted and what could have been done differently, Johri pointed out that solutions which were touted as progressive were more often than not also blatantly exclusive. Citing India’s “digital-first approach” to vaccine rollout as an example, Johri pointed out not only the well-known digital divide and tech illiteracy that often plagues already-marginalised groups, but also the fact that these very groups are also known to be more susceptible to misinformation and distrust due to their limited access to trustworthy sources of information. Adding the fact that women tend to deprioritise their own health to the mix, this confluence of known factors adds up to a discouraging picture of a situation that could have been avoided had the right voices been consulted at the decision-making table to begin with.

Given the same question, Dr. Phionah Atuhebwe (WHO-AFRO) underscored her fellow panellists’ point that all of the challenges identified in this session predate COVID-19, and should have been preemptively accounted for. The continued exclusion of pregnant and lactating women from vaccine designs and trials, for instance, only fueled the fires of uncertainty, misinformation, and distrust throughout the COVID-19 vaccine rollout. The African continent in particular houses a young population with a significant number of young women of child-bearing age, and questions about side effects for pregnant women and potential complications with fertility in the future quickly morphed into deterrents. This was exacerbated by sociocultural norms which award decision-making power to men in most households; Atuhebwe noted that men were in fact comfortable with receiving vaccinations themselves but frequently barred the women of their households, particularly their wives, from getting vaccinated due to a fear of “lineage discontinuity” in the event that the vaccine resulted in infertility for women.

Echoing Ayisi’s example of Ghana, Atuhebwe noted that healthcare workers elsewhere in the world had expressed similar reservations to the initial vaccine rollout, and the gendered nature of the health workforce necessitated the use of a gender lens to understand these barriers to immunisation. The deprioritisation of women’s health by both women themselves and society at large, similar to Johri’s findings in India, further exacerbated the situation. Atuhebwe’s team found that many women did not travel to vaccine centres not only due to logistical difficulties, but also due to fear of contracting COVID-19 at these centres and bringing it back to their children. Notably, in situations where their children required medical care, these women took necessary precautions such as masking and brought their children to seek treatment.

“Can you point us in the direction of gender-related learnings from COVID vaccines that can inform either further COVID vaccine rollouts or routine childhood vaccinations?”

As the panel discussion drew to a close, Schwalbe steered the conversation towards actionable suggestions and potential solutions by addressing the above question to Goulding, who offered three final points. To begin with, Goulding stressed the need to keep in mind the importance of social factors in the midst of exciting scientific innovations. “When you’re focusing very much on trying to understand a new disease, it’s all about the science and sometimes you forget about the social contexts,” she pointed out with a reminder of the gendered inequalities that have created a silent pandemic in tandem with COVID-19 such as the increase of gender-based violence, early child/forced marriage, and school dropouts for girls.

Secondly, Goulding reminded policymakers and campaign designers of the critical need to engage with community organisations, especially women’s organisations which prioritise the kind of gender analyis that is needed to support program design and implementation. She cited Fiji as an example, noting that women’s organisations were able to weather three cyclones in addition to the COVID-19 pandemic to carry out gender analyses which supported the campaign to reach out to women and explore issues surrounding access to services, travel costs, and understanding the benefits of the vaccine. This community engagement has had tremendous success, with over 71% of the island’s population now double-vaccinated.

Finally, Goulding reminded everyone of the bigger picture beyond COVID-19, and the need to continuously support immunisation innovations for gender and health. She noted with pride Australia’s contribution to the development of the HPV vaccine to prevent cervical cancer, and the recent WHO announcement that a single dose of the vaccine is now enough to provide full protection. Amidst all the challenges faced by those working on the COVID-19 vaccine rollout, this served as a timely reminder that such work does make a significant difference to the lives of women and girls.

With an abundance of audience questions streaming in, Schwalbe presented the topics of making sex- and gender-disaggregated data mandatory and reaching the unreached to the panellists for further exploration.

“Why isn’t the WHA doing anything to make gender/sex-disaggregated data a requirement? Why is the WHO finding this a challenge and why can’t it be a priority from the start of a policy framework?”

Schwalbe posed the above question to Goulding and Bigio as speakers affiliated with member-states. Goulding noted that despite the vast majority of her peers acknowledging the importance of sex- and gender-disaggregated data, many are conscious that COVID-19 has strained health systems beyond capacity and are wary of enforcing additional requirements. Bigio called for a continual “demand signal” in the form of consistent and sustained calls for disaggregated data to show that there is interest and utility in the exercise.

“How can we build an engagement of women’s groups and girl-led/centered organisations into this process as we think about gendering programming?”

Johri and Atuhebwe provided examples of good practices on this question, with Johri sharing an emergency response service she and colleagues were involved with in India’s early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Harking back to her earlier comments on known barriers to digital access and tech illiteracy amongst key populations, Johri emphasised that this intervention was designed with these challenges in mind and mobilised 29 civil society organisations to design a service that reached over a million people within the space of 100 days and illustrated that the best solution is not always the “highest” tech or “fanciest” app. Atuhebwe drew on her experience with the HPV vaccine rollout in a number of African countries such as Rwanda, Malawi, Liberia, and Ethiopia, where campaigns proved effective with women’s and girl’s groups as opinion leaders in the effort to engage the target audience through peer-to-peer education.

“Are any of you aware of efforts or can describe some best practice about reaching the trans community?”

This question noted the significance of what might very well be the first universal adult vaccine rollout in modern history, and the conspicuous absence of gender-disaggregated data beyond the traditional male/female indicator. Schwalbe noted that the lack of replies to this question served as an answer in and of itself, and acknowledged that “we do have to start walking the talk on thinking about gender as a little bit more diverse than sex”.

For her final question, Schwalbe asked panellists what one thing they would stop, start, and continue with regard to gender and immunisation. Three key themes emerged from the rich and varied answers given by the speakers:

Returning to close out the session, Allotey shared some reflections for panellists and participants alike to carry with them moving forward, stressing the need for both sex- and gender-disaggregated data to better analyse and understand the power dynamics behind the challenges identified in this webinar. She called on those present to “keep interrogating and pushing those who hold accountability to be accountable” in the process of ensuring sex- and gender-disaggregated data collection. Finally, Allotey urged audiences to keep in mind the power of community organisation and the importance of sharing best practices in the quest to move our work forward as a collective.

Tiffany Nassiri-Ansari sits on the Secretariat of the Commission and serves as a Research Assistant at UNU-IIGH.